Perkins Smart Brailler

Adding feedback and interaction to a classic braille writer.

A brailler writer with smarts. Using it, students learn to control each braille dot themselves, with the help of audiovisual feedback and behind-the-scenes sensors.

A brailler writer with smarts. Using it, students learn to control each braille dot themselves, with the help of audiovisual feedback and behind-the-scenes sensors.

The Challenge

Transform a classic braille writer into an interactive experience. Create a transitional braille learning product avoiding the friction of low-tech or distractions of high-tech.My Role

I led experience design for the project, collaborating with an industrial designer, and engineers from various disciplines. I also developed the package, braille and print instruction manual, and tutorial and game content.Perkins School for the Blind is an institution renowned for serving blind and low vision students. It also has a product division, known for sponsoring and developing many of the products used by the blind and low vision. Classic braille writers (imagine a manual typewriter) were the best and most cost-effective way to learn braille. However, these couldn’t compete with the digital distractions that face students and busy teachers. Could adding a dash of digital help the classic brailler serve value? This project worked with this hypothesis, developing a new braille learning device by enhancing Perkins’ most popular braille writer.

The project was a case study in working iteratively. Throughout the project, we were careful not to spend too much time in the design, build, or test phases. Instead, we cycled through each of these activities. We’d take our best prototypes to the field, learn what we can from a range of users, then come back to the studio. We then discussed what we learned, and went back to the drawing board to tackle whatever was still challenging us. These were broad strokes at first, defining the product. Later it was solving unique problems and adding refinement. At the end of each phase, we’d finalize building prototypes. As time went by the prototypes went from paper and foamcore to 3D printed prototypes, then production assemblies with working hardware.

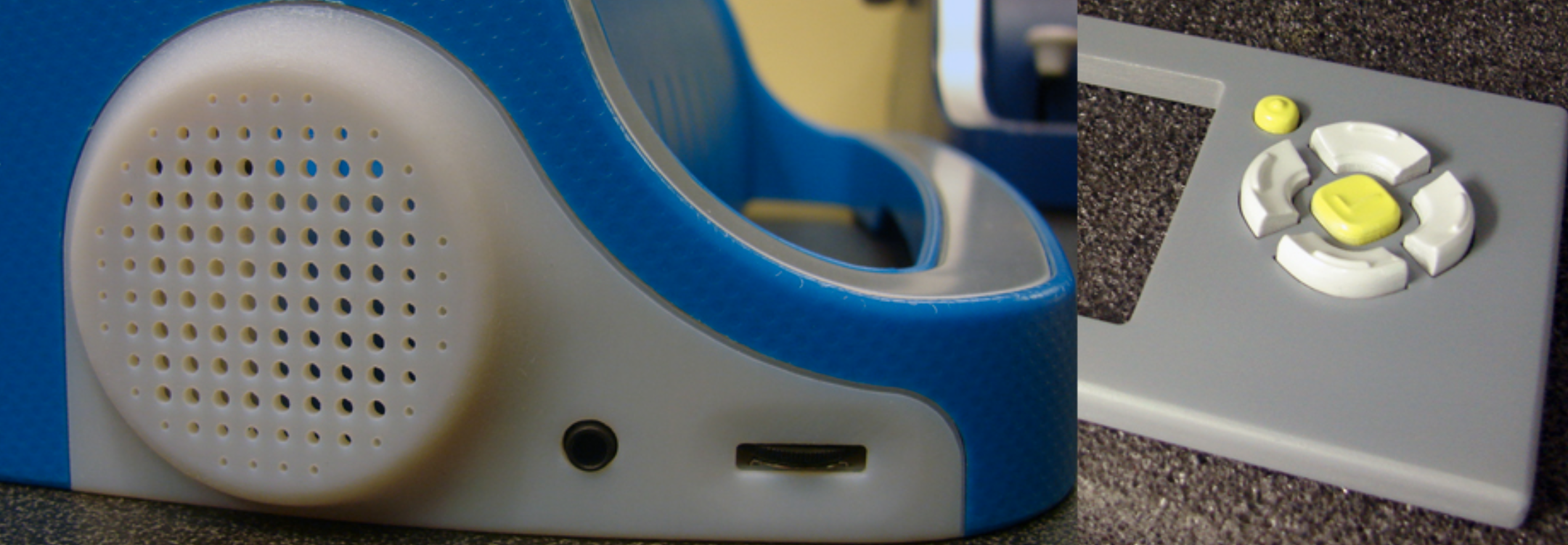

Augmenting an existing device was challenging. As anyone who’s rehabbed an old house or classic car knows, retrofitting has its challenges. Basic things weren’t basic. We needed to develop mechanical-electrical-digital systems to reliably detect the device state: things such as keystrokes on the braille keys, the positioning of the cursor and paper, and the use of a unique “erase” key that mashes erroneous dots back into the paper.

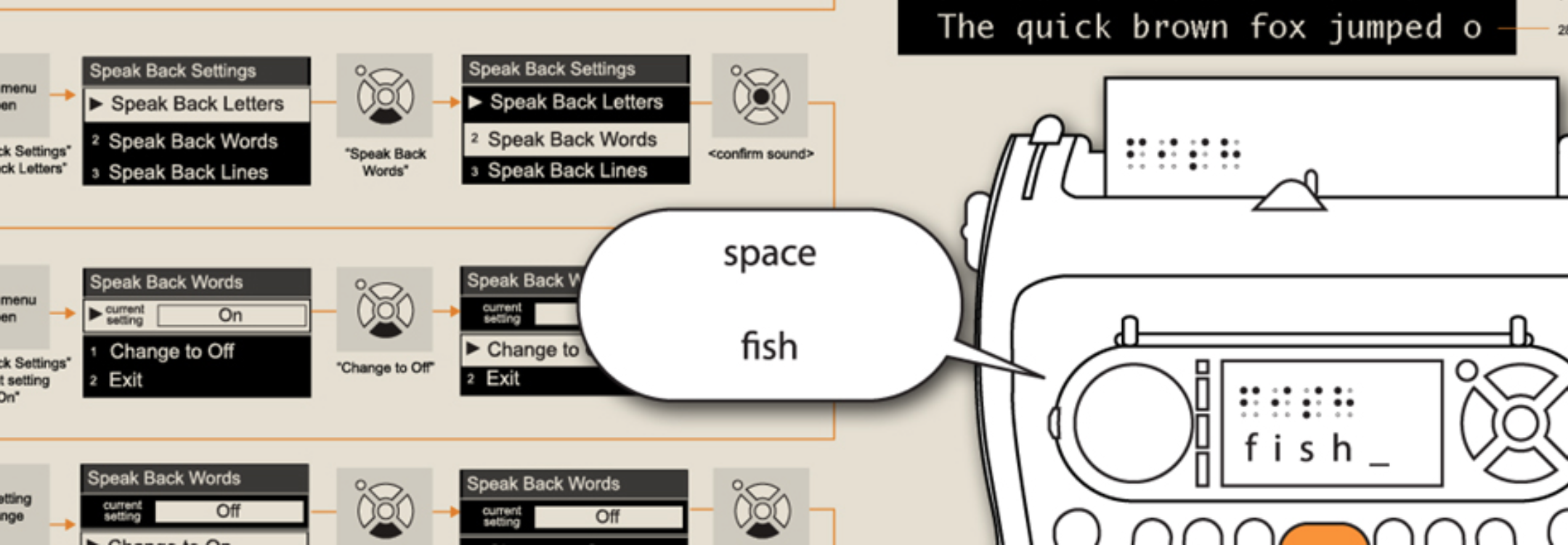

Unique hardware challenges cropped up regularly. Things such as ensuring the device audio was discernible over mechanical sounds. Making sure the digital text matched the embossed text. Making sure the device could keep up with the fastest student. Recognizing the paper’s position at all times. Helping users do things such as insert new pages. For each of these issues, we started a design/build/test cycle.

Retrofitting made the new digital and physical product design seem easy. Finding a place for a battery? Developing a simple UI structure? Ensuring the physical controls are touch-friendly? I won’t say these were easy, because they required careful attention and solid thinking. But generally, they were straightforward.

The project was an exercise in accessible and inclusive product design. The product truly needed to work for everyone—the blind, all sorts of people with low vision, those with auditory and mobility challenges, non-English speakers, a people of varying age and skill levels. All interactions needed to come through clearly to those with specific needs. Most of the special accessibility features took the form of quick-change settings, accessible directly with hardware buttons. This ease of access kept specific affordances from imposing a burden on all users and enabled co-operative activities where multiple users could share a device.

We were surprised to discover the product’s socializing effect. Braille writing is usually solitary, but audiovisual feedback made it a group activity. We observed that parents and teachers would gravitate in from further out to see what was going on. This effect seemed strongest with siblings, who are naturally wired to share and compete. We took this as an extremely positive validation of the basic concept, and we were hopeful that these widening circles would support every braille learner.

More than 5,000 Smart Braillers have been distributed in the US and across the world.

We conducted field research in several schools and student homes across the US states to understand the world of the braille learner, and that of supporting roles such as parents and teachers.

We conducted field research in several schools and student homes across the US states to understand the world of the braille learner, and that of supporting roles such as parents and teachers.

Here’s a feature sheet that tied functions to individual personas. This level of depth allowed us to design a product inclusive to all learners. This was critically important as vision impairments come in many forms and on different timelines.

Here’s a feature sheet that tied functions to individual personas. This level of depth allowed us to design a product inclusive to all learners. This was critically important as vision impairments come in many forms and on different timelines.